Great Films You Need To See – Sorcerer (1977)

This is my latest contribution to The Big Picture, the internationally recognised magazine and website that offers an intelligent take on cinema, focussing on how film affects our lives. This piece about William Friedkin’s criminally underseen 1977 existentialist thriller Sorcerer was written as part of The Big Picture’s Lost Classics strand, although I am including it within my list of Great Films You Need To See.

Unwittingly foreshadowing the fate of its four displaced protagonists, William Friedkin’s existential follow-up to The Exorcist was doomed the moment a certain lightsaber-rattling space opera arrived in cinemas from a galaxy far, far away.

Still Friedkin’s most enigmatic and idiosyncratic film, Sorcerer’s bewitching spell deserves to be cast far more widely

Sorcerer (1977) has been cited by some as the beginning of the end for the New Hollywood movement. However, a giant nail had been hammered into its coffin several weeks earlier with the release of George Lucas’ Star Wars.

In light of this new paradigm of droids, Death Stars and Darth Vader, it’s no great surprise the film bombed on its release and disappeared without trace. That said, Sorcerer was (and still is) one of the most unashamedly offbeat big budget films ever released and was always going to be a tough sell.

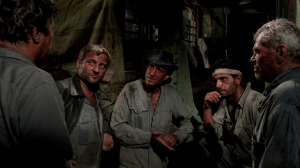

Mexican assassin Nilo (Francisco Rabal), Palestinian terrorist Kassem (Amidou), fraudulent French businessman Victor Manzon (Bruno Cremer) and New Jersey gangster Jackie Scanlon (Roy Schneider) weigh up their options in Sorcerer

Although Friedkin insisted it wasn’t a remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s classic The Wages Of Fear, financiers Universal Studios and Paramount Pictures didn’t share the same opinion, changing its name to Wages Of Fear and re-editing the picture for international release.

The plot is certainly familiar. Four criminals – a Mexican assassin (Francisco Rabal), a Palestinian terrorist (Amidou), a fraudulent French businessman (Bruno Cremer) and a New Jersey gangster (Roy Schneider) – flee the scenes of their respective crimes and end up in a squalid Dominican Republic backwater working for a dodgy oil conglomerate. When one of the firm’s wells is blown up by ‘terrorists’, the desperate quartet sign-up to drive two truckloads of nitroglycerin across more than 200 miles of unforgiving jungle to put out the resulting blaze and pocket a big payday. The only problem is the dynamite is highly unstable and one false move could lead to an abruptly explosive end.

Friedkin has never been one to do things by half and employed the same guerilla style of filmmaking that won him an Oscar for The French Connection (1971) to down and dirty effect for what the director declares is the most important film of his career.

In his autobiography, The Friedkin Connection, he regales how scenes filmed in Jerusalem for the film’s globe-trotting first reel were given added authenticity by a real-life terrorist bombing that took place near to the shoot. In true Friedkin fashion, he made sure to train the cameras on the chaos that was ensuing rather than getting the hell out of there.

This is nothing, however, compared to what comes later in the film. Five years before Werner Herzog dragged a steam ship over a hillside in Fitzcarraldo (1982) in the name of art, Friedkin risked life and limb by having the trucks cross possibly the most dilapidated bridge in the world. The panic-inducing drama as the trucks swing violently back and forth over a raging torrent through almost Biblical levels of rain is almost unbearable to watch and is given extra power by Tangerine Dream’s nightmarish score.

Death and violence seep out of every frame and Friedkin takes an unholy pleasure in stripping hope away from his damned characters at every turn. The look of madness that creeps into Schneider’s eyes as their journey descends further into hell is startling and the hallucinogenic final reel is genuinely unsettling.

Still Friedkin’s most enigmatic and idiosyncratic film, Sorcerer‘s bewitching spell deserves to be cast far more widely.