Four Frames – The Grey (2012)

This is my latest contribution to The Big Picture, the internationally recognised website that shows film in a wider context. Throughout December, The Big Picture is running a series of articles on ‘winter’. This piece is part of the Four Frames section, wherein the importance of four significant shots are discussed, in this case from Joe Carnahan’s under-appreciated survival thriller The Grey.

By the time Joe Carnahan’s The Grey was released theatrically in 2012, its star Liam Neeson had seemingly devolved from being an award-winning dramatic actor to a geri-action star in search of the next dunderheaded blockbuster.

Indeed, Neeson had starred in Carnahan’s previous movie, an ill-advised big screen take on 80s TV show The A-Team (2010) wherein the Irishman stepped into George Peppard’s shoes to play the cigar-chewing Hannibal Smith.

Nothing, therefore, suggested their follow-up to The A-Team was going to be anything but more of the same. However, The Grey was as surprising as it was riveting when it arrived and gave Neeson a role he could finally dig his teeth into whilst still playing the sombre man of action he had become synonymous with.

Set in the harsh wintry environs of Alaska, John Ottway (Neeson) is employed to shoot wolves that threaten an oil drilling team. A flight home goes horribly awry when bad weather brings the plane down and Ottway and a handful of others must do what they can to survive not only the intense cold, but also the equally unforgiving wolves that see the group as their next meal (“they’re man eaters; they don’t give a shit about berries and shrubs”).

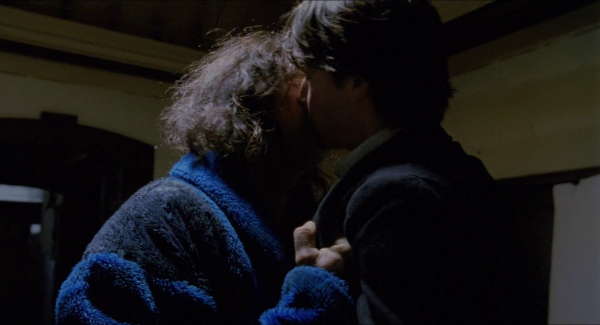

When we first meet Ottway, he is a broken, suicidal figure who has taken a job “at the end of the world” as he sees himself as “unfit for mankind”. The film cuts between flashbacks of Ottway and his wife in happier times and the Irishman penning a suicide note to her before intending to kill himself with his own rifle. That he stops himself from going through with it after hearing the howl of a wolf is an intriguing precursor of what’s to come.

In spite of his suicidal ideation, it’s notable that Ottway’s first instinct is survival when the plane starts going down in what is a truly terrifying sequence.

The very real threat posed by the wolves is laid bare in chilling fashion throughout, not least of which during one particularly unnerving night scene when the survivors first encounter their nemesis. At first one wolf can be seen in the firelight, but soon multiple sets of glowing eyes are visible; accompanied by increasingly hostile snarling.

The fellow survivors are a disparate bunch, as you might expect from a film such as this, but the talented cast of ‘those guys’ such as Dallas Roberts and Dermot Mulroney make the most of Carnahan and Ian MacKenzie Jeffers’ (on whose book this is based) egalitarian script and form a bond that is both believable and affecting as one by one they perish.

There’s a nice parallel between the survivors and the wolves as Ottway stamps his authority by putting down a challenge by Frank Grillo’s hot-blooded oil worker shortly after explaining how the ‘alpha’ wolf ruthlessly deals with pretenders to his rule.

While there is no shortage of action, in particular a buttock-clenching scene in which one of the remaining survivors must first fling himself from a cliff edge onto a nearby tree to enable the others to traverse the canyon by a very precarious rope, The Grey is also notable for its contemplative and philosophical approach.

A poem written by Ottway’s father is uttered throughout and as he faces what looks to be his final encounter, shards of glass and a dagger taped to his hands, its words gather new meaning: “Once more into the fray… into the last good fight I’ll ever know; live and die on this day… live and die on this day…”.

Ottway’s visions of his wife also reveal themselves as something more, while a scene late on – brilliantly played by Neeson (the director had apparently urged the actor to channel his grief over the death of his wife Natasha Richardson) – finds the character desperately calling for divine intervention and, after none is forthcoming, he says resignedly: “F*** it, I’ll do it myself.”

Dissenting critics have mystifyingly scalded the film for its metaphysical leanings, claiming them to be unnecessary – which is to miss the point entirely. These are presumably the same reviewers who bemoan the lack of depth in today’s bigger budget fare. Roger Ebert, on the other hand, was deeply affected by what he saw, so much so that he had to walk out of another screening (something he had never done before).

Right until its shattering cut to black, The Grey digs its fangs into you while also packing an emotional wallop that’s as sublime as the wild Alaskan landscape.