Review – The Last Exorcism Part II

The word “last” clearly shouldn’t be taken literally in this lazy and derivative money-grabbing sequel that puts the ‘moron’ into oxymoron.

The word “last” clearly shouldn’t be taken literally in this lazy and derivative money-grabbing sequel that puts the ‘moron’ into oxymoron in The Last Exorcism Part II

Made for a pittance, 2010’s The Last Exorcism was something of a surprise hit with both horror-lovers and critics. Its plot was a clever twist on a tried and tested genre and at its core was a genuinely impressive performance by the relatively unknown Ashley Bell as troubled Nell Sweetzer.

The filmmakers (including producer Eli Roth) looked to have shaken off the tired and stale tropes of the found footage format for the first 70 unnerving and taut minutes, lost their bottle in the final reel and retreated to tried and tested genre staples, undermining everything the movie until that point had worked so hard to subvert.

The fact the film made a big profit was undoubtedly the driving force behind this ill-judged follow-up, whose title is as hilarious as it is non-sensical. Once again produced by Roth, directing duties have this time fallen to Canadian Ed Gass-Donnelly in what was presumably hoped to be a career breakthrough.

The opening credits are essentially a flashback to the events of the first movie, wherein a disillusioned preacher (played by Patrick Fabian) works with a documentary film crew to chronicle his final ‘exorcism’ and expose the whole practice as nothing more than religious hokum. The subject is Nell, whose father is convinced is possessed by the devil; but little do the preacher and film crew know that this particular case of satanic possession is all-too-real.

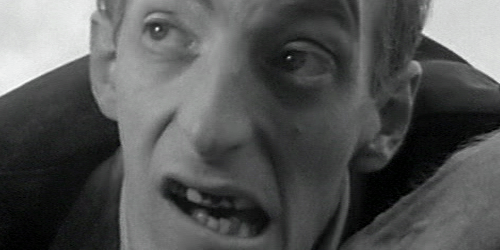

Picking up a short time afterwards, Part II‘s creepiest moments occur in the first few minutes when a demonic-looking Nell is discovered hiding in a couple’s kitchen. Alas, the promise of the opening scene dissolves quicker than you can say “Pazuzu”, and we’re very swiftly subjected to a game of spot the rip-off.

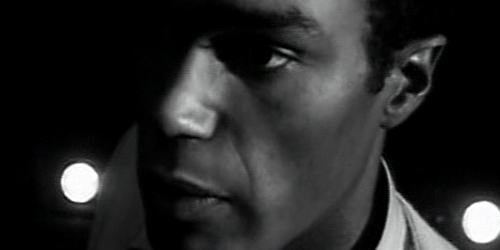

Nell is sent to a home for girls run by the kindly Frank (Muse Watson) and gradually comes out of her shell. She makes friends with several of the other girls, gets a job as a chambermaid and even develops a budding romance with bland hotel worker Chris (Spencer Treat Clark).

However, you know something bad’s going to happen when Frank reassures Nell by saying: “Whatever you’re running from won’t find you here.” And you definitely know it’s a case of famous last words when Nell happily declares: “There was a darkness, but now it’s gone … none of it was real.”

It almost goes without saying that Nell’s going to pay for wearing lipstick, being attracted to Chris and listening to rock ‘n’ roll (the devil’s music, lest we forget), but the film doesn’t even try to subvert what we know is coming from a mile off. What scares there are (next to none) are ruined by the lazy cliché of being accompanied by explosions of sound. A film’s always in trouble when is has to resort to that.

Bell gives a far better performance than the film deserves. Without her it would have been a total car wreck and it’s to her credit her turn brings to mind Sissy Spacek’s Carrie and Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby. It’s a good job too, as the largely forgettable supporting cast only seem able to alternative between looking confused, evil or dumb.

To make matters worse, the door is left open for a sort of Omen III: The Final Conflict-style sequel which sounds about as much fun as being decapitated by a sheet of glass. Still, The Last Last Last Exorcism as it should be known could hardly be as demonic a waste of time as this.