It’s Day 3 of the ‘Debuts’ Blogathon, hosted by myself and Chris at Terry Malloy’s Pigeon Coop. Today’s contributor is Ewan from Ewan at the Cinema. Ewan keeps it simple, concentrating on reviews of new releases, modern classics and more leftfield choices. Each of his reviews are well thought-out and give you plenty of food for thought and I highly recommend you get yourselves over there.

Jean-Luc Godard

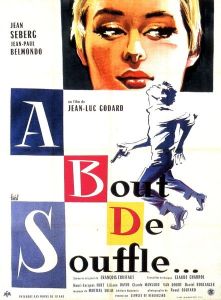

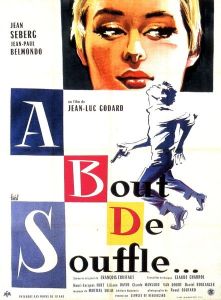

Breathless (À bout de souffle) (1960)

There were, in 1960, certain ways of making feature films wherever you were in the world; methods that had been built up over the preceding half-century of filmmaking and which continue to endure to this day in mainstream cinema.

The key thing about this debut film from young French film critic Jean-Luc Godard is that few of these methods were followed, though such rulebreaking might have had less effect had the film not also been an enjoyable pulpy retrofitting of familiar American imagery. One of Godard’s famous aphorisms, which he attributes to D.W. Griffith, is that “all you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun”, and here indeed there’s a girl (Patricia, played by the American Jean Seberg) and a gun, generally wielded by gangster Michel Poiccard (played by Jean-Paul Belmondo). He’s on the run, she hooks up with him: that’s all you really need to know about the plot.

The key thing about this debut film from young French film critic Jean-Luc Godard is that few of these methods were followed, though such rulebreaking might have had less effect had the film not also been an enjoyable pulpy retrofitting of familiar American imagery. One of Godard’s famous aphorisms, which he attributes to D.W. Griffith, is that “all you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun”, and here indeed there’s a girl (Patricia, played by the American Jean Seberg) and a gun, generally wielded by gangster Michel Poiccard (played by Jean-Paul Belmondo). He’s on the run, she hooks up with him: that’s all you really need to know about the plot.

Referencing pulpy B-movies from the States was part of a deliberate strategy by a number of like-minded French critics making their first films all at the same time, loudly rebelling against the staid cinema of their fathers’ generation. This movement became acclaimed as the nouvelle vague (or ‘French New Wave’), and if François Truffaut gained a lot of early attention for his Les Quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows, 1959), it’s Godard who set out a lot of what made this New Wave memorable and which define its lasting legacy.

In his films in particular you can see a youthful passion for cinema combined with formal innovations showing a blatant disregard for classical techniques, often informed by a self-consciously revolutionary politics. Even in this very first film of Godard’s can be seen a lot of what would later come to dominate his style.

In his films in particular you can see a youthful passion for cinema combined with formal innovations showing a blatant disregard for classical techniques, often informed by a self-consciously revolutionary politics. Even in this very first film of Godard’s can be seen a lot of what would later come to dominate his style.

First, let’s talk politics. Not party politics (of which there’s plenty as Godard gets older), but la politique des auteurs. That phrase translates as ‘the policy of authors’ in French, but the common translation of the term in the English language has been ‘the auteur theory’, thanks to Andrew Sarris’s writings from the 1960s onwards. It was a critical idea of Truffaut’s that helped to shape the way that the New Wave first developed as a director-focused movement, but I think its value has been overstated.

In many ways it’s a provocation like the Dogme 95 manifesto of Lars von Trier (and others), a way of focusing attention and signalling a change in methods from the mainstream. It has also helped to focus critical attention on the French New Wave, though similar changes in filmmaking practice were taking hold in various parts of the world at the same time, whether it be the Italy of Antonioni and Pasolini, or the American films of John Cassavetes.

In many ways it’s a provocation like the Dogme 95 manifesto of Lars von Trier (and others), a way of focusing attention and signalling a change in methods from the mainstream. It has also helped to focus critical attention on the French New Wave, though similar changes in filmmaking practice were taking hold in various parts of the world at the same time, whether it be the Italy of Antonioni and Pasolini, or the American films of John Cassavetes.

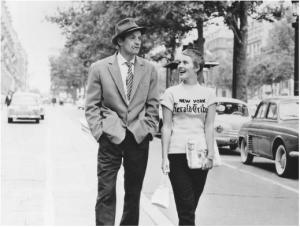

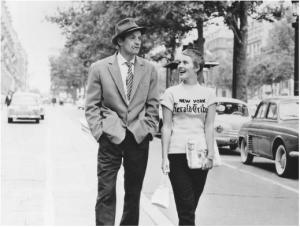

The ‘auteur theory’ is alluring for Godard’s films in particular, which often seem like such personal expressions, but even in this very first film he liked to expose the mechanics of filmmaking. It starts here with Michel addressing the camera directly as if the audience is a passenger in the car he’s driving. There’s also a sequence later on when Michel and Pauline are walking and talking down the Paris streets, and all the passers-by can be clearly seen turning and staring at them and the camera (this scene also neatly illustrates both the simple energy of just capturing a spontaneous and improvised scene directly — an energy that suffuses the film as a whole — but also the technical changes in filmmaking that had in part opened up the way for the nouvelle vague, as smaller and more portable cameras became available).

Only a few years later, in Le Mépris (1963), Godard would kick off the film by showing the cameraman Raoul Coutard backed up by his crew dollying down a track filming the actors while Godard read out the credits, and this kind of breaking of the fourth wall would become a regular feature of his films.

Only a few years later, in Le Mépris (1963), Godard would kick off the film by showing the cameraman Raoul Coutard backed up by his crew dollying down a track filming the actors while Godard read out the credits, and this kind of breaking of the fourth wall would become a regular feature of his films.

Not unrelated is Godard’s habit for improvising dialogue. The script here is credited to Truffaut — and there was creative input too from Claude Chabrol (another critic and nascent filmmaker) — but that script was only apparently the outline of the film. The scenes as they play in the film were as often scribbled out by Godard himself, shortly before filming took place, and this would often be his method in future.

Yet this personal inspiration (that of the auteur) is one that draws heavily on other texts and influences. There’s scarcely a scene that doesn’t quote the American cinema he so loved — whether it’s Michel standing in front of a poster of Humphrey Bogart (The Harder They Fall), tracing his fingers around his lips as he imagines Bogart to do, or mimicking Debbie Reynolds’ melodramatic mugging in Singin’ in the Rain as he sits around Patricia’s apartment. These are just two examples, though. There are many more allusions to Hollywood movies, and it’s a habit that Godard would only extend, taking influences and presenting decontextualised quotations from film and literature like a magpie, until eventually entire films of his (such as Histoire(s) du cinéma) become playful interrogations of sources. Godard, more than most directors, has always remained a critic.

Yet this personal inspiration (that of the auteur) is one that draws heavily on other texts and influences. There’s scarcely a scene that doesn’t quote the American cinema he so loved — whether it’s Michel standing in front of a poster of Humphrey Bogart (The Harder They Fall), tracing his fingers around his lips as he imagines Bogart to do, or mimicking Debbie Reynolds’ melodramatic mugging in Singin’ in the Rain as he sits around Patricia’s apartment. These are just two examples, though. There are many more allusions to Hollywood movies, and it’s a habit that Godard would only extend, taking influences and presenting decontextualised quotations from film and literature like a magpie, until eventually entire films of his (such as Histoire(s) du cinéma) become playful interrogations of sources. Godard, more than most directors, has always remained a critic.

This first film also exposes some common techniques and themes that Godard liked to use. There are those long-takes of characters talking that do away with the classical shot-reverse shot construction, so here you have Patricia questioning Michel in the car while you hear his replies from off-screen. There are the sequence shots of couples in cramped domestic spaces bickering about meaningless topics, trying to escape one another (and the film’s frame), but never succeeding. There’s the fecklessness of male desire, and its betrayal by women — it’s interesting in this regard that Patricia was explicitly noted by Godard as an extension of Seberg’s character Cécile in Bonjour Tristesse, another young woman isolated in a world of unconstrained chauvinist desire (and she’s great in both films).

Yet if there’s often in Godard’s films a self-important male figure (like Jean-Pierre Melville’s author at a press conference near the end) espousing generalisations about women, it’s also often accompanied and set in juxtaposition to lacerating self-critique (Godard himself plays an informer in the film). And I haven’t even mentioned the famous jump cuts.

Yet if there’s often in Godard’s films a self-important male figure (like Jean-Pierre Melville’s author at a press conference near the end) espousing generalisations about women, it’s also often accompanied and set in juxtaposition to lacerating self-critique (Godard himself plays an informer in the film). And I haven’t even mentioned the famous jump cuts.

But in 1960 none of this would mean very much if it was just another young director showing off his Brechtian or cineaste credentials, as so many like to do. The point is that around this time there weren’t any mainstream filmmakers doing this stuff. Sure, there were occasional isolated examples of these techniques beforehand, but for Godard (as for like-minded young directors of the era such as Cassavetes) it was just the way he made films.

It shows most of all in the looseness and jazzy rhythms of this debut, more akin to documentary than to feature films of the period. Godard would extend his interests as his career progressed, becoming ever more esoteric as his meaning became more opaque, but he was never more accessible than in this first, exciting despatch from the front lines of a new wave.

Meanwhile, head over to Terry Malloy’s Pigeon Coop where Keith from Keith & the Movies is covering John Huston’s noir classic The Maltese Falcon (1941). Get yourself over there now!

As for me, check back tomorrow, when Cindy from Cindy Bruchman will be stepping behind the radio mic for her take on Clint Eastwood’s 1971 debut Play Misty For Me. See you then!